Modern life feeds us the line that happiness comes when we follow our desires. If you have a dream, then chase it. If you have an itch, then scratch it. If you have an urge, then satisfy it. But what if what made us happy only ever left us wanting more, or simply created an ever-bigger hole to fill? Instant gratification – the holy grail of our superficial, accelerated age – is increasingly only a click away; and yet, as we are liable to discover, its effects are frequently over just as quickly – bringing a feeling of emptiness and further intensifying the original craving. Will the next bite of the apple be enough? Is this appetite for consumption becoming addictive, even destructive? Can one have too much of a good thing?

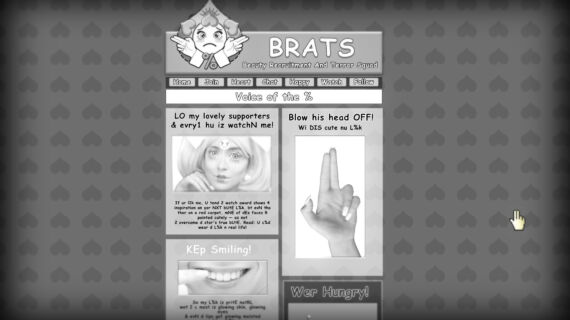

Rachel Maclean’s Feed Me is a parable of the pleasures and perils of indulgence, and a wicked, waspish skit on a world where greed is good, and it’s OK to give in to every temptation and whim. Extravagance and excess, those seductive ugly sisters – whispering to the avarice in our soul, always eager to tickle the sweet spot of the contemporary cultural palate – are, one can hardly fail to notice, also signature features of Maclean’s artistic palette; evident in her obvious love of dressing up and in the multi-layered digital confections with which she drapes and decorates her work. Although these colourful computer-generated effects apply a fantastical candy-coated surface, Maclean lays it on equally thick with make-up, costume and prosthetics: older tricks of the theatrical trade that enable her to appear as multiple characters in a parade of show-stopper performances. These characters, in turn, run the gamut of current fashions, fixations and tastes: the pre-teen social media fanatic, and the silver-fox media entrepreneur; the starry-eyed child entertainer whose golden ticket to fame and fortune is also the meal ticket for the behind-the-scenes mentor, fairy godmother or industry svengali. Feed any of these creatures a line, and they know exactly how and when to act – and how to convey themselves in the best possible light. This frenzy of self-regard (and barely-concealed self-interest) is all frivolous sound and fury but its froth of sweet nothings has a dark and bitter aftertaste, as Maclean lambasts the commercialisation (and sexualisation) of childhood, and deftly skewers a corresponding turn towards infantilisation in adult behaviour. As we continue to feed the monster of contemporary consumerist desire, Maclean’s film is an indelible reminder of all the little monsters that are born in its wake.