Encounters that Resonate: Foxfire Eins by Jayne Parker

Rosa Tyhurst

Rosa reflects on Jayne Parker’s quartet of musical interventions in the present moment — exploring the power of non-verbal communication, gesture and dance.

Projects

It is often claimed that the cello is the musical instrument that most intimately mirrors the human voice. Its soulful resonant timbre spans four octaves, similar to the range of you and I. Its low C is at the bottom range of a basso profundo and its high C is near the range of a coloratura soprano. Its form is proportional to that of a human body, the top scroll reaching the head of its seated player and its spike by her feet. I’ve always thought that Man Ray’s iconic 1942 photograph Le Violon d’Ingres [Ingres’ Violin] should be Le Violoncelle d'Ingres [Ingres’ Cello]. Like the image suggests, when one plays a cello it becomes part of one’s body. When I grew up playing the instrument in secondary school its form felt daunting, echoing the reality of my changing pubescent body. Playing it, I was revealing something of myself; the way we sat, the sounds we made together, it felt like I wasn’t alone.

The collusion between instrument and human body is notable in the films of UK filmmaker Jayne Parker, who in 2000 produced a series of musical performances for the camera that explored touch, gesture, sound and performance, and where the instrument (a cello, played by Anton Lukoszevieze) became a proxy for another body. These works, collectively known as Foxfire Eins, which is also the name of the first film in the series, were a continuation from Parker’s previous films that explored translations of the body (often her own) and her attempts to “try and see and feel what a body can do.” For Parker, this resulted in films of herself disgorging metres of intestines before attempting to knit with the lumpen mess of flesh (K. (1989)); diving into a swimming pool again and again to exhaustion in The Pool (1991), and grappling with an uncontrollable mass of eels in Snig (1982) and RX Recipe (1980). Prior to 2000, Parker’s films predominantly used fragmented music, silence and sound, often ambient and environmental, such as the thuds of dancers moving together or whispered cooking instructions. Foxfire Eins is a series of films featuring Lukoszevieze playing musical compositions by contemporary composers Helmut Oehring, Volker Heyn, Morton Feldman and John Cage respectively, marking a transition in Parker’s work that began with a collaboration with pianist Katharina Wolpe in the film Thinking Twice (1997). My intrigue lies in the choice of these compositions; the corporeal metamorphosis Parker orchestrates, transitioning from the human body – including her own – to the bodies of instruments. Moreover, the resonance of this series with the wider choreographic medium of ‘dance for camera’, an experimental genre that first emerged in the 1960s, allows for a reading of interplay between artistic mediums. In the following paragraphs, I will expand on these choices, offering additional insights into Parker’s deeply layered work and tracing the lineage that permeates her output.

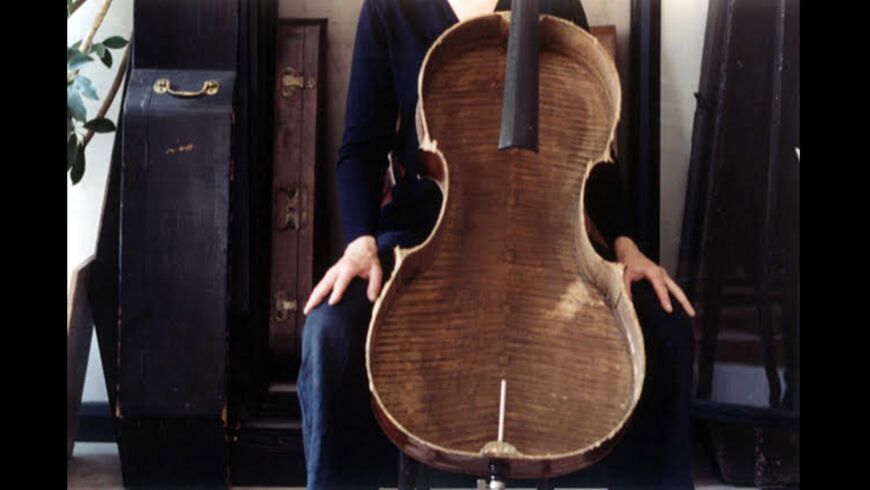

Parker is absent from all but one of the Foxfire Eins works. In Blues in B Flat she appears, mute, sitting in a luthier’s workshop with an eviscerated cello resting between her legs. This violent image appears at the start of the film, it presents the interior of the soundbox – the nexus of the cello’s sound – gaping wide open and silent, just before we see a male musician fill his cello with vibrations. Composed by Volker Heyn in 1981, ‘Blues in B Flat’ pits loud blazing tones and mechanical rhythms against silences. Heyn worked in factories during the 1970s and took inspiration from the metallic sounds he encountered, later attempting to recreate them in his compositions. In Parker’s film, we see close-up shots of the fine white horse hairs of Lukoszevieze’s cello bow passing over sharp steel strings. It slides up and down the neck of the cello, landing near the bridge so he can play sul ponticello, creating a glassy rough sound. A gentle touch along the strings reveals hidden harmonics, and long legato notes are interspersed with shots of the cavernous dismembered cello in the workshop. I imagine playing that cello, the sound melting away to nothingness. Heyn was known for his scores to be almost ‘unplayable’ and near the end of the composition a second bow begins to play underneath the strings in opposition to the first. Lukoszevieze holds this interloper like a weapon, his left hand curled like a fist, in juxtaposition to the delicate poise of the right. The bows criss-cross each other like knitting needles. It is perhaps no coincidence that this is the only film Parker appears in, her presence and position recalling conductor Thomas Beecham’s pernicious quote “Madam, you have between your legs something which could bring pleasure to millions and all you do is sit there and scratch it”. It highlights a connection between the cello and a sexualised body, along with the latent power relationships within classical music, echoing that of society.

A certain masculine physicality is also present in Parker’s Foxfire Eins, which features a piece composed by Helmut Oehring. Lukoszevieze grapples and tussles with the score, his hands deftly travelling over the cello. He plays ‘hammer on’, a technique when notes are played by forcefully pressing down on the strings only, and pizzicato, a plucking of the strings. The right hand that is usually confined to holding the bow begins a complicated dance with the left. At a pivotal moment, Lukoszevieze seizes the cello’s neck, silencing its voice with a firm grip, reminiscent of a hand muffling speech. The close-ups evoke echoes of Yvonne Rainer’s 1966 Hand Movie, a silent black and white film of a hand moving. Shot in a hospital bed whilst recovering from surgery, her prone body is replaced by her mobile hand, which performs increasingly complex movements until it relaxes into a flat position. Oehring was the child of profoundly deaf parents and his first language was sign-language. For him, music is gesture and movement, an experiment on how sound can be witnessed non-aurally and performatively. Watching Lukoszevieze play Oehring’s piece I recall the ache of my own body playing the cello; the divots on the tips of my fingers from repeatedly pressing down on metal strings, the cello’s curved edges pressing into my fleshy inner thighs and my right arm held out at an angle to my body. Parker’s film embodies these sensations, further implicating and integrating the viewer and their body in the work.

In Projection 1, Parker adopts a more graphic strategy, mirroring Morton Feldman’s intricate score comprising boxes on three levels that refer to the high, middle and low registers. Tempo, timbre and duration are indicated by pitch, but dynamics are left to the performer’s discretion. Parker pulls in close to the cello strings, deliberately engaging the instrument's structure which is intersected by the bridge and the cello bow. I think of the work of Agnes Martin and her geometric compositions, and the dance scores of Merce Cunningham – numbered grids with rough shadings in the corners indicating movement, durations and directions. Notably, Feldman’s collaborations with Cunningham during the 1960s exemplifies a period where musicians, filmmakers and choreographers converged, working together to blur boundaries between artistic mediums. Works tailored for the camera, exemplified by Rainer, Cunningham and Trisha Brown, introduce a temporal elasticity, a space where time can expand and contract. The camera lens created a unique space for performance; we can witness things that we would miss on the stage or at the concert. Maya Deren, an early influence on Parker, and progenitor to dance for the camera, underscored the connection between movement and film. Through the lens of the camera, a symbiotic relationship emerges, where both filmmaker and dancer share responsibility for shaping the choreographic narrative. Indeed, this narrative is familiar to Parker; in 1997 she made two projects commissioned for TV as dance films. The Reunion and The Whirlpool poetically captured intense sensations, that of shifting power relations, and the spectacle of an underwater dance. To return to Projection 1, near the end of the piece Lukoszevieze’s breathing becomes audible. Parker reminds us of the body at work, and the physical exertion of these seated performances.

Recurring imagery ricochets throughout Jayne Parker’s work, some of which I’ve previously outlined. Within all of her output, the act of touch emerges as paramount: whether it’s the rough wiping away of blood, the delicate wrapping of a human leg in gauze, or the forceful pressure of a bow on strings. Similarly, she is interested in the transmutability of forms, whether it be between human and animal forms, as in The Pool, or in Foxfire Eins, where the boundary between human and object blurs. Watching Parker’s work is a visceral act. As she shapes space, form and time, she places demands on her viewers and their own bodies.

Following the Foxfire Eins series, Parker continued her collaboration with Lukoszevieze. He performs for the camera in Trilogy: Kettle's Yard (2008), a series of three films set in Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge, and The Oblique (2018) in which she revisits Volker Heyn’s score Blues in B Flat. Most recently Lukoszevieze provided the sound track for Secondary Action (2023), playing John Lely’s composition The Harmonics of Real Strings, III; this film animates a series of drawings Parker made as a student in 1977. Now offscreen, alongside Parker, Lukoszevieze’s performance is further translated. His physical actions are replaced by the gestural shapes of the animated drawings. We must listen and watch Parker’s films carefully, they act as a reminder of the power of non-verbal communication through music, gesture and dance. And in our present moment, finding these ways to communicate feels more important than ever.

--

Rosa Tyhurst lives and works in the UK and is curator at Gasworks, London. She has previously held curatorial and research positions at Nottingham Contemporary, Spike Island, KADIST, and the de Young Museum. Her writing has been published in Art Monthly, Hyperallergic, and elsewhere.