Excavating the Body

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona

Awardee of the Michael O'Pray Prize 2023 Natasha Thembiso Ruwona explores Ashanti Harris’s Black Gold.

Projects

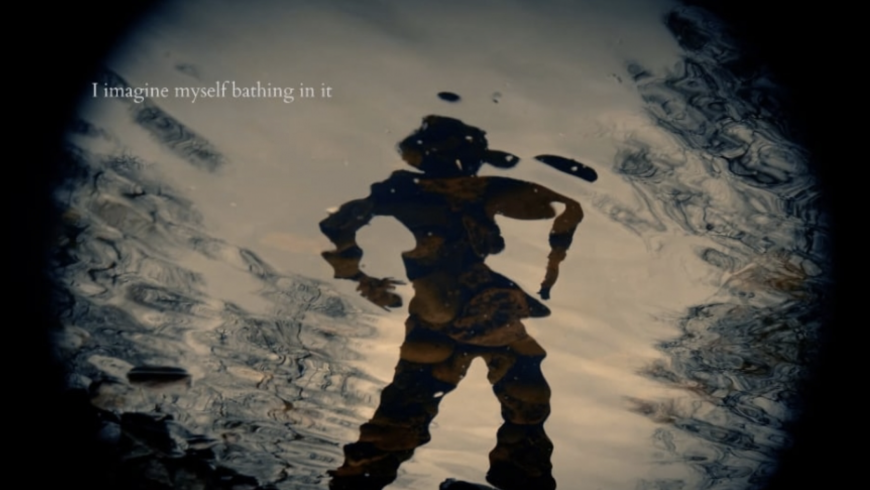

Gentle lapping brings us to the shore or returns us to the water’s surface. Ashanti Harris’s film Black Gold begins with a statement: ‘I’ve been thinking about pressure.’ These opening, urgent words give the viewer space to locate their body in the here and now. Harris focuses our attention not only to the pressure on our bodies, but also the production of oil itself. By naming both this internal and external pressure, we are reminded that the body is itself a malleable material constantly shaped by environmental factors; for Ashanti, a person, like oil, is formed through an amalgamation of its environment across time and space. As opposed to the fluidity of the figure we see moving on screen – where hands fold, unfold, touch and separate, as if guiding the narrator’s words – we also become aware of what it means for a body to become fixed under pressures unseen but felt. Physical gestures made by the onscreen dancers give a sense of the materiality of oil: I picture in my mind the substance held in the dancer’s hands as they move on screen, as it slips through their fingers, meeting the wrist and sliding down their arms, dripping over their body. The figure becoming this substance, something wet and fluid, a shapeshifter. In Black Gold it is through the body that we come to understand oil.

Next, we are placed in the world of Drexciya. The word appears on the screen almost like a whisper or an omission from the spoken narration – the word references the underwater world invented by the titular Detroit techno duo. Their mythology is of a Black Atlantis: where pregnant slaves who were thrown overboard during the Middle Passage gave birth to babies who learned how to breathe underwater. As with Drexciya and the processes in the formation of oil, the bottom of the ocean is a place of mystery and transformation. Where life and death meet. Lost in time.

In Black Gold, oil is mythical too – a substance that is mentioned but never visible. Despite Harris’s uncertainty about whether she had ever ‘seen real crude oil’, the artist creates a speculative description of its textures, its colour palette and how it might sit on her skin, the smell and its ‘energy’. This feeling is what gently guides the film. At one point, Harris speaks of submerging herself in the oil, but was only once ‘invited to do so’ (an oblique statement about who is invited and by whom). In the film, her body becomes a vessel for the oil to take shape – although weighed down by its history, she remains light.

The film was further enriched by a Q&A after its premiere, during which it became clear the importance of Harris’s research and personal excavation of her memories in the film’s development. It was revealed that the film is grounded in the artist’s research into the relationships between Guyana (where she was born) and Scotland (where she currently lives). Harris also spoke of the discovery of oil reserves in Georgetown in 2015 that led to the ‘twinning’ with Aberdeen in 2019, where the oil company’s head offices are now based and is now considered the ‘oil capital of Europe’. This contemporary relationship with oil, in Harris’s work, is inseparable from the extraction of lives between Scotland and the Caribbean during colonisation, a history that Black Gold fixes firmly within the present.

Harris also spoke of holding the tensions of these histories within her body. In the film, dance is a physical reminder that she is here now, telling us this history again through her own story. The use of movement within the film could be read as an attempt to reconcile these difficult histories and relationships, and which continue to form part of her personal geography. Partaking in a body-based practice is clearly part of releasing this tension, or the ‘pressure’ which is endured. In the case of Black Gold, oil is the catalyst, a gateway to the past and present. A return to the body, to feeling, is to heal and to acknowledge what and how we know.

The artist communicates her process through an embodied approach that differs from the common practice of research as one of information gathering and fact collating, and which might often be detached from emotions and feeling. Harris’s film is therefore not a historical account of her research into oil or the extractive relations between the countries, but a physical response to her research which situates her body as a vessel for the past, present and future, and across geographies. The process of gathering this research is translated through the body, as if the artist becomes the research itself, transforming into its very material – oil.

Harris describes the process of making work as digging, of physically exerting oneself through ‘searching’ and of ‘burying’ the past. A burial is a moment of ‘honouring the past’, to ‘feel’ and to be with community. A burial creates a physical connection to the earth and to the body via, as she names it, an ‘energy exchange’.

Harris also shared the difficulties she encountered during her early attempts to create the film, which were often the result of various pressures she was feeling at the time. The artist recalled the advice given by therapist and writer Foluke Taylor to audience members during an online talk, asking them to stop interrupting the ancestors and let them finish their sentences. Taylor applies this idea of interruption as a process for overcoming the feeling of pressure to stop working or of being consumed by self-doubt when starting a creative endeavour. The artist is always in dialogue with her ancestors, those who have come before her and continue to be part of her work.

Black Gold is personal, yet collective. It speaks to the challenges of inhabiting a diasporic body, one which is held in tension and in dialogue with people, places and time. This is further expressed through the metaphor of Harris eventually becoming oil in the film: a ‘physical thing’, as she describes it. Black Gold feels like it is part of a process of healing for the artist; with this in mind, the work becomes the ‘physical thing’ too – the response, the tension and the pressure manifested and perhaps eventually reconciled. The pressure that we have come to know through the film is transformed: as Harris turns into oil, her body becomes an undoing of time and space.

Ashanti Harris’s Black Gold premiered at Fringe of Colour Films in Edinburgh, June 2023, as part of the festival’s wider commissioning programme.

—

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona is an Awardee of the Film and Video Umbrella and Art Monthly Michael O’Pray Prize 2023.

The Michael O’Pray Prize is a Film and Video Umbrella initiative in partnership with Art Monthly, supported by University of East London and Arts Council England.

2023 Selection Panel

Terry Bailey, senior lecturer, programme leader, Creative and Professional Writing, University of East London

Katie Byford, Projects Manager, Film and Video Umbrella

Kondo Heller, poet, writer, and filmmaker

Juliet Jacques, writer and filmmaker

Chris McCormack, associate editor, Art Monthly

Image: Ashanti Harris, Black Gold, 2023