FVU Frames: Sophie Cundale

Ellen O'Donohue Oddy

We sat down with Sophie Cundale to discuss the making of The Near Room and how she came upon the film's key concepts: Muhammad Ali's Near Room and Cotard Delusion.

Projects

Sophie Cundale doesn’t like to pin down her films. When I ask her about the meaning behind a gesture, frame, or sound, she tells me that “it is hard to put into words something that takes the language of film.” So instead, our conversation about her latest work The Near Room revolves around the viscerality of filmmaking, and the poetic flexes of a boxing match. The film is partially shot in one of South London’s oldest boxing gyms, Lynn AC, not far from Cundale’s first solo exhibition at South London Gallery, opening on 6th March 2020, the week after our conversation. Whether we realise it or not, these conversations around Cundale’s early thinking behind the film, how she got professional boxers and artists in the lead roles, and her own relationship to Lynn, can’t help but spill into the poetic. Maybe, that’s because of the nature of boxing.

“Muhammad Ali was a poet as well, he released a poetry album,” she tells me, and I’m surprised I didn’t already know this. Though given Ali’s reputation as one of the most perceptive, untouchable sportsmen, his poetic achievements are far from surprising. This is most evident in Ali’s concept that gives Cundale’s film its title. The Near Room is a space that Ali would glimpse in the depths of a fight, a psychological cliff-edge, with “neon, orange and green lights blinking, bats blowing trumpets and alligators playing trombones, snakes screaming. Weird masks and actors’ clothes hung on the wall, and if he stepped across the sill and reached for them, he knew that he was committing himself to his own destruction.” (1)

When Cundale first read this quote in George Plimpton’s Shadow Box, it “held onto me, I couldn't let it go. Then, other things started to attach itself to it.” Things such as death and grief, specifically “the relationship between the living and the dead.” A subject that, for Cundale, is as impossible to articulate with language as her film. She is certain that “to try to universalise, generalise, or rationalise any experience of grief or death is a bad idea.” As such, the film looks instead towards two concepts: Ali’s Near Room and Cotard Delusion.

Cotard Delusion is a psychological state whereby a living person believes they are dead. Cundale first heard about Cotard Delusion in a newspaper article about the experiences of a person who had recovered from the condition. She got in touch with them, and they were happy to discuss the nature of the condition with her. “It’s an afterlife, but you’re still alive – and that can be applied to so many things, so many experiences. So that’s what brought those two things together. This idea of The Near Room that Ali had, and the proximity that he has to it in a fight, where if he stepped in, he’d be changed forever. That’s really alluring somehow. Cotard Delusion is a very understandable delusion – it’s completely logical. If everything around you has changed, or if you’ve been dehumanised by everything around you, or if you’re in really unfamiliar territory, then you might start to put together proof for your non-existence.”

Like the story behind her interaction with the person who had recovered from Cotard Delusion, Cundale prefers to give meaning to her film by speaking in the anecdotal. This makes sense, given the nature of her process as an artist and filmmaker is led by the practical. Her main characters, for instance, were not written until she knew who was going to be playing them: the artist Penny Goring as The Queen, and the professional boxer John Harding Jnr. as The Boxer. Similarly, the boxing gym she chose to shoot in was a film set already: “Lynn AC in Camberwell is one of the oldest boxing gyms in South London. I went to a load of boxing gyms over the years and always tried to imagine scenes in them. I started going to Lynn just to train, and I could imagine filming the scenes in there. I started to think about lighting and smoke machines, and who from the gym might want to be involved. The scene in Lynn is where the film starts.”

Cundale’s dual perspective, both training and directing in the gym, is palpable when you watch the film. She sees something in boxing that goes beyond athleticism, beyond competition:

“You always have different personalities in boxing, that’s what makes the narratives make sense. How they walk to the ring, to what music, what they say before they get in – what costume they’re going to wear. There are all these details that create a character, and a boxer is a character. They are performers in a theatrical sense. All those details that precede the fight are all there to build in our minds, as a watcher, a holistic and compelling identity. That adds to the excitement and the pain you might feel as well, through them.”

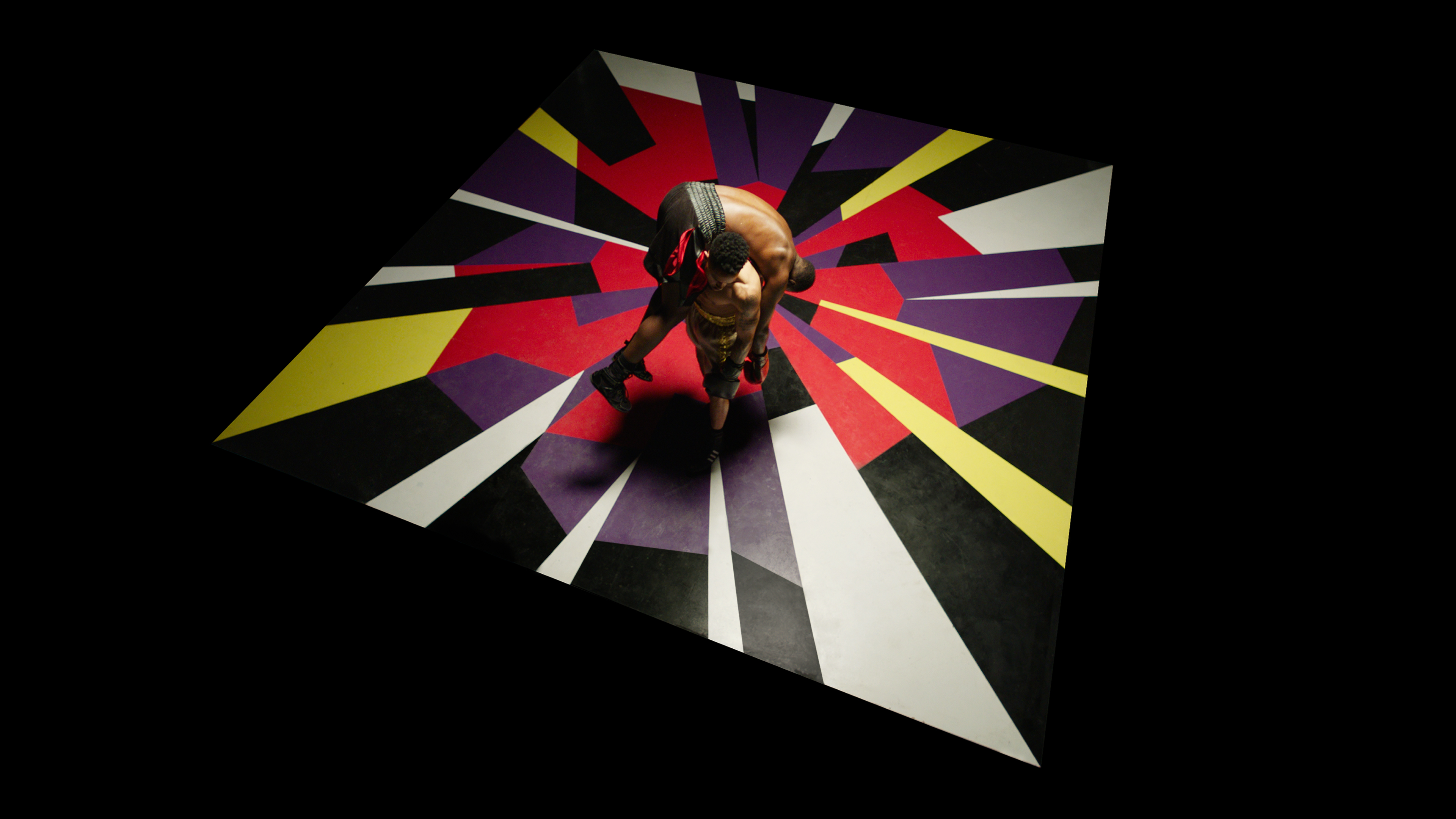

The film contains one fight scene, which is drawn upwards into a moment of choreography. This moment is centred around the boxing clinch, a move that sees a boxer wrap their arms around their opponent to create a pause – which Cundale sees as a moment of both co-support and also getting the upper hand. In directing the fight scene, devised and choreographed by cast members John Harding Jnr., Mark Tibbs (professional trainer to John), Ahmet Patterson and Choreographer and Movement Director illyr, it was important to keep the clinch central.

“We wanted the fight to feel even – right throughout, until the end. When you’re watching it, you’re not sure which direction it’s going in – and that’s what’s compelling about a match that’s perfectly balanced. For me, the clinch was always the most important part to get across – to elevate, physically.” This moment of dance is the exact opposite of what you expect. And in creating this moment, it is as if Cundale is peeling back the surface of boxing. For many people, boxing is too violent to watch. But in Cundale’s film, and in speaking to her, it is so clearly wedded to the poetic: it’s about timing, skill, intelligence, reading movement, and responding to those readings.

“A lot of fight scenes of boxing on film don’t focus on the clinch – it’s not a moment that is held up in any way. For me, that’s a tender moment in the film – the violence is not in that moment, it’s everywhere else. I am aware of the thought-process of somebody who hasn't been involved in boxing – so I tried to edit the fight with them in mind. There’s no sound in the fight – it’s just the score, John’s voice and Mark’s voice. The sound of a fight can be overwhelming.”

The contradictory energies within the clinch feel more than pertinent with a film that, despite being centred on psychological slipperiness, on the cusp of afterlife, is also about support, through moments of rescue and release. These moments cement the film’s core theme of grief, and the alternate world that The Boxer steps into, where he meets The Queen, played by artist Penny Goring.

“Originally The Boxer and The Queen were the same character. Then, they branched out from each other, they got their own lives, and stopped being the same person. I saw Penny Goring reading her work at AutoItalia and knew that she was The Queen. Afterwards, I wrote for an entire year without meeting Penny, then finally when I was confident enough in the work we met a couple of times at her flat to talk about the film. She said she would do it. I was so lucky. I'd prepared for her to say no, but also had this feeling that because I’d written it so much for her, that she would feel an attraction to it.”

“As for The Boxer, I went to a press conference at The Dorchester hotel to see what these events were like in real life. This one was for Dillian Whyte and Joseph Parker. I knew Mark Tibbs would be there as he trains Dillian, so I psyched myself up to talk to him afterwards. He was so generous from the start and gave me his number. We met a few times in East London near the Peacock Gym to talk about his boxing experiences. I realised that Mark should really be in the film, and also asked him to help me with casting The Boxer as I knew I couldn’t do it alone. I outlined the character for him and straight away he said, “I’ve got your boxer.”

“I felt like the Boxer would be in a similar way only written once I knew who they were. Penny was in my mind from the beginning of writing The Queen and was also basing it on Juana la Loca (Joanna the Mad) so I had that construct. With The Boxer I had a lot of different boxers’ experiences that I’d read or listened to in person but this was still a cacophony. Mark knew straight away it would be John, but I was still thinking ‘OK, I need to keep this process quite open’. I knew that once I met the boxer that I'd be able to write their part better as I would hear their voice, it would become more of a co-write as they'd also be bringing themselves to it. John came in for a casting and it was obvious that he was the boxer."

The fact that the two central characters, though on the surface so different, were once the same character, isn’t a huge surprise. Perhaps this is because the relationship between The Boxer and The Queen is bound by the fact that the two must come together: he releases her to a death, which returns his psychological state back to the present.

“There’s not really a conclusive interpretation. And there’s not a point. And that’s OK. The Boxer coming to see The Queen at the end, has marked her end and his beginning – and at the beginning, she marks his end. John as The Boxer says it in the film: “We can’t tell whether it’s the beginning or the end that’s holding us together’. But, in terms of the form of the film, I’m hoping that there’s an openness to it.”

The film does indeed end with the promise of momentum. In fact, a very similar momentum that it begins with – we’re in the same location, seeing the same people, hearing the same sounds – except, it’s not a loop. Something has changed. So, I ask her, is there going to be more?

“No. It’s finished. I just wanted that feeling. As if it’s a pilot episode of a never-to-be-finished saga.”

Endnotes

1. George Plimpton, Shadow Box: An Amateur in the Ring (2016)

–––

Watch FVU Frames: Sophie Cundale, BTS footage shot and edited by Anita Safowaa here

See Sophie Cundale's The Near Room at South London Gallery from 15 August – 13 September 2020. Book your visit here

Ellen O’Donohue Oddy is Communications Manager. She is also a writer, speaker and critic, working at the intersection of art and literature, specifically after the birth of the internet.

Images: FVU Frames: Sophie Cundale, BTS footage shot and edited by Anita Safowaa

The Near Room (2020) by Sophie Cundale is commissioned and produced by Film and Video Umbrella (Producer Laura Shacham) with support from Arts Council England, South London Gallery, Bonington Gallery, Curator Space and The Gane Trust.