Local Time

Patrick Langley

Patrick Langley considers the concept of travel and its representation in Layla Curtis' Antipodes

In the year since the launch of Antipodes by Layla Curtis, how has the planet changed? In geological terms, a year passes like nothing. Rocks abide by vaster calendars than those which shape our seasons. The seasons shift, but they always shift. The Earth’s rhythms – the daily rise and fall of light, the lunar pulsing of the tides – are as intricately calibrated as the cogs in a Swiss watch. Clouds form and disperse, deserts rearrange themselves. None of this is news. What, then, might a year of looking at the planet look like? What might the vigilant gaze of a sequence of paired webcams reveal, not just about the things that they individually observe, but our global situation?

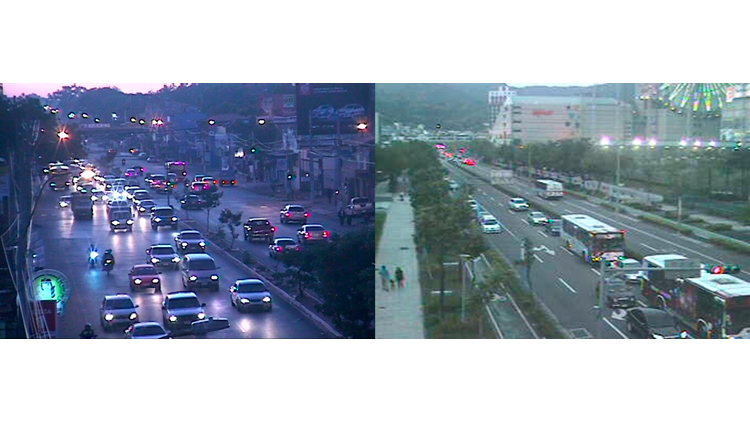

Antipodes is built around a deceptively simple premise. Take two points on the earth’s surface, as far away from each other as it is physically possible for them to be, and watch them, unblinkingly, for a year. It is an exercise in attention, a kind of aesthetic surveillance; it is also a study of opposites. Antipodes are both locations and anti-locations. They are united by the mutual fluke of their geographical positioning. But distance, as the project demonstrates, is not always the same as difference. Through the pairing of these public cameras – cameras which have no awareness of the yearlong conversation in which they are taking part; which are, in a sense, being ‘hijacked’ – remarkable parallels emerge, and suddenly that gulf of separation (roughly 7,926 miles, if you were to travel directly through the earth) collapses, becomes no separation at all. As the sun sets in one camera, it rises in another. São Joaquim’s loss is Sakurajima’s gain. The orange dusk that hangs above the urban clutter of Porto Alegre abruptly shelves to pallid dawn where it meets the Fukuoka sky, but notice how the dark hills in the distance merge with those of their antipodean counterpart, and, rather than the diametric opposition one might expect from such far-flung localities, there is a sense of seamless contiguity, a blending of horizons.

I sit and peer across a bay on Moneron Island bay. (King Edward Point is sunk in darkness: a black antipode.) Not much is happening right now, it seems, but the archive tells a different story. Flicking through stills of the preceding year, perceiving changes in weeks instead of minutes, I observe how the foliage changes from green to beige as the seasons turn, and watch the white snow steal upon the landscape as the blue bay pales to frigid turquoise over the course of several time-lapsed months. It is deeply unlikely that I will ever visit this place, and yet I am able to ‘be there’, to experience proximity from afar. In a world where acts of visual teleportation are as easy as this, the word ‘location’ acquires a double meaning: both the specifics of particular places, and the technological systems that enable us to locate ourselves within a global context.

‘Travel’, too, has acquired a more complex meaning. Physically speaking, we are not going anywhere by sitting at our desks and staring into screens, and by experiencing the world remotely, as ocular tourists. Yet in imaginative terms, it could be argued that we are indeed travelling, or ‘roaming’ – the term used by telecommunications companies when a customer travels afar but remains wirelessly (often exorbitantly) connected to their original phone network. It’s become a cliché of modern tourism that, through Google Earth or YouTube, we experience the places visit long before we ever reach them: consequently, our experience of the Eiffel tower, say, is not one of awe or romance, but simple déjà vu. In order to know where we have come from, where we are going, we rely on atlases and maps – arguably to a fault. The landing page of the Antipodes website shows us a reimagined atlas in which, rather than a totalising, satellite-eyed vision of the planet, we are presented with the coexistence of polarised worlds, one in black lines, one in red, one upright (according to the atlases I was raised on) and the other inverted, with no indication as to which is the ‘real’, privileged worldview. Faced with this ambiguous geography, in which, through a simple act of cartographic collage, our world is turned upside-down, and that which was once singular is now shadowed by its opposite, we are reminded that places are always defined by what they are not, as much as what they are. Night has fallen in your hometown, and it is daytime somewhere else; and as you sweat through the height of summer, it is deepest winter elsewhere.

Maps make implicit claims to objective knowledge. To map a place is to know it in its superficial entirety; to know a place entirely is to master it. But a map can only ever be a snapshot. In physical terms, the earth is in a constant state of flux; in human terms, we are perpetually altering the landscape, digging, demolishing, bridging, building, puncturing its crust and polluting its atmosphere. Maps, by necessity, flatten the world. As the poet Elizabeth Bishop wrote in ‘The Map’: ‘Topography displays no favorites; North’s as near as West.’ By abstracting the landscape, in turning territories into maps, clarity is gained and rootedness lost, and the traditional markers by which we situate ourselves (Bishop’s ‘North and West’) are rendered arbitrary, equidistant, subsumed within the cartographic worldview.

Antipodes intentionally disrupts the notion of fixed perspective, and the results can be disorientating. Logging onto the website and picking a pair of cameras, I feel as though I am accessing these places almost physically, not simply viewing them; at any rate, I find myself imagining the physical sensation of being there, in two antipodes at once – midday sunshine and deepest night, the blustery rain of monsoon season and the dry, stunned heat of a dusty city. The images are not the HD footage that might ordinarily encourage a feeling of sensory immersion by dint of spectacular clarity; rather, they are small, pixelated camera-feeds prone to interference and obstruction. Snow forms a wall of blankness. Raindrops pebble the lens. Sometimes the feed is garbled, dissolving into pixel-blizzards or indecipherable stripes, and other times it cuts out altogether (with apologies): ‘We seem to be experiencing some technical difficulties. Rest assured our guys are working on it.’ These moments of disruption, obstruction and seizure remind us that networks don’t always run smoothly, and that the technology we use to understand the world can also leave us unable to situate ourselves. Overwhelmingly, however, the message is one of continuity – of places, certainly, but also time.

In watching antipodean points over the cyclical course of a year, these paired extremes remind us of the grand, global sweep of the ongoing moment: the planetary present tense in which all places simultaneously exist, regardless of their current place in the diurnal cycle. By emphasising visual similarities where we might expect harsh disjuncture, Antipodes at once conveys a sense of border-hopping internationalism, and the deep uncertainty of finding oneself, of ‘knowing where you are’, in a global context. However fixed in one particular place, however firmly located, we are always haunted by the possibility of elsewhere. You are here, says the GPS system, and it pins you to a map. But you could always be somewhere else.

–––

Patrick Langley is an editor at Art Agenda and a contributing editor at The White Review. His debut novel Arkady, was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions 2018.

This text was originally published on the occasion of Layla Curtis’ moving-image artwork Antipodes (2013-14). From March 2013 to March 2014, Curtis’ Antipodes website observed the planet through a series of paired webcams at opposite ends of the globe. Antipodes by Layla Curtis is commissioned by FVU, in association with Spacex. Technical support by Cuttlefish. Supported by Arts Council England.