Quarantaine: Taking Possession in Three Acts

Dominic Paterson

Dominic Paterson (The Hunterian, The University of Glasgow) explores Georgina Starr's Quarantaine within the context of avant-garde cinema and theory.

Projects

Prologue: Film Possessed

Quarantaine is an artist’s film by Georgina Starr. It was commissioned through a partnership between Art Fund, Film and Video Umbrella, The Hunterian, Glasgow International and Leeds Art Gallery; Art Fund have gifted the first edition of the work to The Hunterian for its permanent collection through their Moving Image Fund. To introduce Quarantaine with reference to these facts is already to cast it in terms of summoning and ownership. The work is called for or invoked by certain institutions, but it belongs to Starr as its author, and to a kind of film-making by which artists take possession of that medium. What or who can take possession of film, and by what means, is one of the work’s preoccupations. And it is in its turn possessed or haunted by particular moments in the history of cinema (and visual and aural cultures more widely) where such questions were posed by others.

Quarantaine belongs to a remarkable body of work that Starr has been developing over the past decade in which aspects of alchemy, occult knowledge, literature, music, cinema and pedagogic or instructional practices are mixed together to form a personal cosmology expressed in recurring iconographic, textual and choreographic motifs. Among the elements of that cosmology are images of women blowing bubblegum bubbles as fragile ‘breath sculptures’, sculptural brains (also formed from bubblegum, renamed by the artist as ‘The Pink Material’), allusions to the stages of gestation, birth and childhood, audio recordings of female voices providing instruction, and performed gestures carried out by groups of women in vividly colourful period costumes. These elements have appeared variously in a set of Tarot-like predictive cards designed by Starr, in the artist’s book The History of Sculpture (2013), in performances such as Before Le Cerveau Affamé (Cooper Gallery, 2013) and Androgynous Egg (Frieze Projects, 2017), and in the short films The Lesson and The Birth of Sculpture (both 2016). Starr’s forthcoming novel The Discreet Dash elaborates these motifs into a larger narrative structure, in relation to which Quarantaine might be understood as a partial adaptation.

It is important to note that Quarantaine was conceived and produced in 2019 and early 2020, before its title evoked so inescapably the collective experiences of the coronavirus pandemic. However, the intimations we now can’t help but hear in the title—of the suspension of cultural normalcy, of seclusion from others, of a moment of risk and transformation—are by no means inappropriate to the film. ’Quarantaine’ is the French word for a forty-day period, and is indeed etymologically related to ‘quarantine.’ Starr noted in her initial treatment for the work that in Celtic mythology the beginning of Spring marks a point at which ‘the Spirit Goddesses of the Sun and the Moon can descend to Earth and live as mortals for forty days. It is a liminal dangerous occasion when the barriers between the Earthly world and the Spirit world are temporarily dissolved.’ Quarantaine imagines such porosity taking place within a scenography that draws us from contemporary London into a series of otherworldly spaces within which new identities and new relations are formed.

Act I: Attention! Enter the movie theatre

Quarantaine commences with an iconoclastic gesture. Scanning the cityscape from the vantage of her motorbike, ‘V’ encounters posters bearing the repeated image of recumbent women with legs raised and opened—a pose Starr calls ‘splitzing.’ This image, taken from a cache of historical pornographic photographs Starr found, had been adopted and adapted for a previous work (Splitzing, 2013), with the addition of a bubble emerging prodigiously from the woman’s lips. In obvious anger at the objectification of this female body, our protagonist cuts the limbs from the posters—in the process inscribing her own name, ‘V’, in the negative of the shape made by the woman’s legs—and makes off with them. The act of cutting, so central to filmmaking, is thereby figured at Quarantaine’s outset as a means to contest the representation of women’s bodies and to assert one’s own selfhood. It is a way to make an opening in the body of film itself.

In Quarantaine’s second scene a double invocation sets the main narrative in motion. ‘L,’ a bookish, introverted type in comparison with the combative ‘V,’ is seated on a park bench reading a book of magic. ‘L’ makes an incantation—‘6699’— which seems to call forth ‘V’ who then stashes the arms and legs she had severed from the posters within an opening in a tree. This magical sequence directly invokes the beginning of Jacques Rivette’s inspired, uncategorisable 1974 film Céline and Julie Go Boating. Perhaps the limbs serve to unlock a portal to another world, for soon both characters pass through the tree and into ‘The Grey Reception,’ a purgatorial waiting room in which several other women await an audience with a fortune teller who uses Starr’s Cerveau Affamé cards to predict their fate. ‘V’ and ‘L’ then move through a series of other spaces, from ‘The Solar-Lunar Light Therapy Room’ to a curtained space for learning. There they undergo instruction (or perhaps initiation) under the command of a maternal figure, ‘Pearl Mama One,’ who appears as a disembodied floating head. In a bravura performance by the soprano Loré Lixenberg, Pearl Mama One’s direction of her charges comes in the form of an abstracted vocalisation of Pauline Oliveros’s 1965 electronic composition Bye Bye Butterfly, a piece itself made with an avowedly feminist intent.

To produce Céline and Julie… Rivette invited his two leading actresses, Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier, to co-create its story on set. They did so, in a palpable spirit of playful complicity with each other, through improvisations, surreal flights of fancy and with irreverent treatment of cinematic conventions. As a result, the film is continually upstaged from within, not least when the protagonists find themselves transported to a home within which a family melodrama, loosely based on Henry James’ novel The Other House, plays out repeatedly. Here Céline and Julie alternate in playing one of the roles, hinting—as do other moments of imposture in the film—that they are doubles of each other, and sending up any pretence to naturalism that the scene might otherwise possess.

’All films are about the theatre, there is no other subject,’ Rivette once claimed.

In calling up that pre-cinematic art to take possession of Céline and Julie… in particular, Rivette thus proposed not only a subversion of the film, but also a reversion to cinema’s very entrance into mass culture, at a point where it was particularly close to stage magic and to theatrical techniques. Film scholar Mary Wiles suggests that the parallel worlds Rivette’s heroines visit take us back to a situation of play that is not only associated with individual childhoods but with ’the innocence of an art form, which is shadowed by its theatrical ancestor.’ Quarantaine channels this moment of emergence and hybridity. It is notable that in an early film such as Méliès’ 1901 Dislocation Mystérieuse, for instance, we find visual tricks applied to its central Pierrot figure that prefigure some of those that appear within Quarantaine. In both, body parts separate themselves from bodies and perform their actions independently, conforming to Walter Benjamin’s claim that within the cinema’s capacity to enmesh ‘body space’ within ‘image space’ we face a situation in which ‘no limb remains untorn.’

For Benjamin, the promise of cinema in its early phases was as a means of what he called ‘innervation,’ that is ‘a mode of adaptation, assimilation, and incorporation of something external and alien to the subject.’ Benjamin believed that in a world transformed by technology, and in which human mimetic capacities expressed in childhood play and in theatrical performance risk being overwhelmed by the shock of modernity, film made a space within which embodied, imaginative and crucially collective, adaptation could occur anew. The passages and thresholds that ‘V’ and ‘L’ traverse in Quarantaine lead us back to cinema’s entrance onto the technological and cultural stage, and to theatricality’s haunting of the camera's claims to truthful representation. In Starr’s ‘innervation’ of film, it becomes, again, a space within which to play, and in which to invoke magical animations and transformations.

Act II: Listen! Enter the image

’The dream machine of contemporary entertainment is not just what you dream of,’ Steven Connor notes, ‘it is what you dream with, since it is the machinery of your dreams.’ Highly attentive to the imbrications of subjectivity, technology and imagination, Georgina Starr often practices an incorporation of images, sounds and personae. In her work she has frequently entered the dream machine of cinema in order to perform it differently. One key form of access for Starr in this regard is film’s own incorporation and domestication within television and video. She has spoken of the formative experience of watching films at home with her mother, and of wishing to climb inside the TV and join the action. She put this wish into practice in early works such as Visit to a Small Planet (1994) in which she rewrote and reenacted a Jerry Lewis movie from memory, using a DIY chroma key set up of endearingly limited effectiveness, or in her creation of a character who performs the parts of all the ‘Pink Ladies’ from Grease for the video Frenchy (1996). In The Bunny Lakes (2000-2003) she repurposed films by Otto Preminger and Peter Bogdanovich to address aspects of her own family history. More recently, in the 2007 film Theda, Starr reconstructed lost movies by Theda Bara, prompted by her perception of a similarity between her own mother and the silent era star. And in 2017’s Moment, Memory, Monument she constructed a version of a brain-like time machine from Alain Resnais’ Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968) which viewers could enter one at a time, guided by performers and instructed by a recorded voice, so as to themselves participate in a personalised enactment in the film’s science fiction conceit. In such works, cinema is dragged into the spaces of the home, the studio and the gallery, and incorporated from the perspective precisely of its reception, its assimilation by viewers.

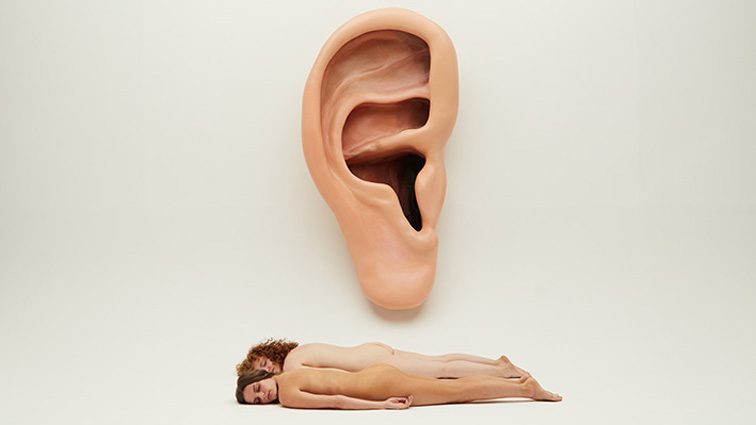

A thread that has run throughout Starr’s oeuvre, from her earliest works up to Quarantaine, is her extraordinary attentiveness to sound. A childhood experience of auditory hallucinations spurred early works that tuned in to the possibility of voices embedded within incidental sound, while acts of overhearing inspired pieces such as Mentioning (1993) which set fragments of strangers’ conversation into musical form. The uncanny plaint of the sound work Mum Sings Hello (1993-2009), in which an answerphone recording of the artist’s mother singing the iconic Lionel Ritchie hit is serially dubbed from cassette to cassette so that it descends with each iteration into howling white noise, locates this investment in listening firmly in relation to the maternal voice. And if Quarantaine enters into the mechanism of film in a way that summons the spirit of early cinema, it does so with the crucial addition of a highly developed sonic dimension - precisely what was lost when film first incorporated theatre. This is palpable in Pearl Mama One’s vocalisations in music and speech, and in the ecstatic choral performance that accompanies a sequence in which formless ‘Pink Material’ oozes and drips (with its intimation of an oral training facilitated by bubblegum). That the passage into Quarantaine’s liminal spaces is at the service of what Starr elsewhere refers to as ‘the birth of female voice,’ is evident in the fact that in the film’s initial sequences, the characters are effectively muted. Perhaps the key image of the film makes clear the preeminence of sound within its imagined world: when ‘V’ and ‘L’ pass from ‘The Grey Reception’ into the spaces of initiation, they do so by climbing naked through a huge ear. Listening affords a second cut into the body of film; within Quarantaine’s universe it is the means by which a sorority attending to maternal callings might be formed.

Act III: Leave the movie theatre

Quarantaine’s heroines pass through successive phases of physical and psychic retraining as the film progresses, with that regimen itself assembled from fragments of actual instructional practices. If the exact purpose and logic of this drilling remain elusive, the viewer is left in little doubt that it is bound up with female embodiment and collective agency. When ‘V’ and ‘L’ reemerge at the end of the work in another reprise of Rivette’s Céline and Julie…, it is back into the ordinary ‘reality’ from which the film first departed. But we can see that the protagonists have been changed by their experience: they have bonded, they converse and laugh together and it is perhaps the illusion of reality that amuses them. And we viewers now see them from an eccentric and changed position of our own, not unlike that implied by another landmark in early cinema from the year 1901. In John Williamson’s The Big Swallow an irate man gesticulates at a camera which moves ever closer to him until camera, tripod, cameraman and all are seen to disappear into his mouth. As if this weren’t startling enough, the film’s final sequence moves back out of the mouth to show the satisfied protagonist. Has he triumphed over the dream machine by swallowing it whole? If so, by what mechanism should we assume we are seeing him now? Have we too been swallowed up into image space? Is there no escape? This example might illuminate Quarantaine’s strategy by contrast: in Starr’s film the drive is for the protagonists to go further inside an image space in which agency is being reassembled, to climb inside and learn to take control.

In 1975 Roland Barthes published a short essay in which he conveyed the pleasure he felt in leaving the cinema: ‘a little dazed, wrapped up in himself, feeling the cold—he’s sleepy, that’s what he’s thinking, his body has become something sopitive, soft, limp, and he feels a little disjointed, even … irresponsible. In other words, obviously, he’s coming out of hypnosis. And hypnosis … means only one thing to him: the most venerable of things: healing.’ If Barthes is wary of the ideological dimension of the viewer’s enchantment at the hands of cinema, he proposes that instead of breaking off from our ‘narcissistic and maternal’ fascination with the screen, we might instead try taking off from it, ‘in the aeronautical and narcotic sense of the term.’ This would mean, he contends, extending our attention—really our desire—from the film screen into the spaces that contain it. It would mean staying hypnotised even as we take our leave of the movie theatre. Quarantaine invites or instructs us to practice just such a passage in and out of the film, to take off within Starr’s imagination as it seizes hold of other imagined and overheard worlds. It cuts into film to hypnotise and heal, to take possession.

–––

Quarantaine (2020) by Georgina Starr is co-commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella, The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, Leeds Art Gallery and Glasgow International with Art Fund support through the Moving Image Fund for Museums. This programme is made possible thanks to Thomas Dane Gallery and a group of private galleries and individuals. Supported by Arts Council England.