On Saturdays the brothers from Aleppo came with the week’s shopping but today was Tuesday and someone was knocking on his door. He considered calling out to ask who it was — what if it was, again, someone at the wrong apartment? — but he wasn’t yet ready to give up walking to his own front door and greeting whoever was there. He shuffled forward to the edge of his chair, extended the left leg to the side, pressed his hands down on his thigh above the stronger right knee, and with a cry of ‘Ya Rabb’ raised himself up.

The knock came from a young man whose features blended into any part of Germany, which made it a surprise to hear the greeting, ‘Marhaba.’

‘Ahlan?’ he said, dismayed to hear the response emerge as a question.

The young man repeated ‘Marhaba,’ and added ‘Abu Mustafa.’

So few people in Berlin referred to him as ‘father of Mustafa’ or even knew that he’d ever had a son by that or any other name. He was ‘Khaled’ or ‘Herr Hamdan’ to almost everyone. Only the Syrians at Shaam restaurant called him by the name this stranger had uttered, and he saw them infrequently now that his knees had made a Mount Everest of the three flights of stairs.

The young man said, in confident though strangely accented Arabic, ‘Do you remember me? Michael?’

He saw him now — the long-lashed blue eyes, the lop-sided smile. Michael, the boy across the street, whose presence had first been announced by a literal lifting of a load. The carpet Abu Mustafa had been carrying over one shoulder from the bus stop to the apartment building had suddenly become almost weightless and he had turned to see a boy standing close behind him, the rolled-up carpet resting on the top of his head.

‘Ahlen, Michael!’ He moved to embrace the man at the same time that Michael extended his hand and then there was the awkwardness of Abu Mustafa moving back and proffering his hand at the moment that Michael moved towards the embrace. But then they laughed, held each other — the pleasure of two bodies meeting in affection after years apart — and Michael entered Abu Mustafa’s home.

He saw the young man’s eyes go to the single chair in the living area, facing the television, and felt shame. The brothers never stayed to socialise. Abu Mustafa was their grandfather’s friend — they brought him groceries every week and carried him up and down the stairs when he had a doctor’s appointment but they had lived their entire lives in Germany and keeping an old man company for a few minutes every week was an obligation too far for them.

‘We can sit in the kitchen,’ he said, and Michael saw this as an invitation to bring one of the two kitchen chairs out to the living area.

‘I put the kettle on. Now that I’m old enough to want a cup of tea,’ Michael said.

When Abu Mustafa walked out of the kitchen with a tray of biscuits and tea Michael was looking at his books. In his first year here, he had made a home of this space — carpets, a mounted shelf for his books, framed Quranic verses and an unframed poster of Damascus that the owner of Shaam had taken off the wall of the restaurant and presented to him. The Aleppo brothers had found him a new radio, the television and a smartphone that had to stay plugged in at all times because it had no functioning battery: all of these came from a website where people listed items they didn’t want anymore. The television usually stayed off because the smartphone allowed him to listen to radio stations from Syria and other parts of the Arab world.

Michael pulled a book from the shelf, one of those Abu Mustafa had brought with him from Damascus. ‘I remember this one. I thought it must be by a Syrian writer.’ He read the title out loud, with the pride of a man who has learnt a new script: ‘Bustan al-Karaz. It’s the Cherry Orchard.’

‘Chekhov is a Syrian writer, of course,’ Abu Mustafa said.

‘Of course.’ He took the tray from Abu Mustafa’s hands and set it down on the table between the two chairs. ‘But where are the toys?’ He made a fist with one hand, extended one bent finger and moved it in rapid rotations while the other hand beat on the surface of the table, sound changing as his palm moved between tiled top, wooden frame and plastic tray.

It took Abu Mustafa a few moments to understand and then he laughed. ‘My instruments. That was long ago.’

‘Instruments, I’m sorry. I always thought of them as toys. I imagined you had been an engineer, that’s why you could use an electric toothbrush to turn empty bottles and baking tools into animated objects.’

How well he could speak Arabic while Abu Mustafa’s German was still so poor after seven years.

‘I was a music teacher,’ Abu Mustafa said. Then, shyly, ‘a musician.’

‘A musician.’ Michael placed a hand on his chest, against his heart. ‘Sometimes at university I thought of giving up Arabic. It was so hard at first. Then I imagined coming back here and being able to understand the things you were saying to me. Which instrument?’

‘Darbuka. It’s a drum.’

‘I know. Do you have one here?’

Abu Mustafa shook his head. However fluent Michael’s Arabic he wouldn’t understand if Abu Mustafa tried to explain that when you leave a life behind you can end up abandoned by some of the things you thought you’d always carry inside. There was a darbuka at Shaam, decorative; it served as a table for a lamp. His friends there had tried to get him to play it once but when his palm beat against its surface he didn’t feel skin touching skin, only hollowness.

‘Who is that?’ Michael pointed to the phone, and Abu Mustafa realised for the first time that Asmahan was singing, had been singing this whole time. Michael said he thought he recognised her voice from all his visits to this apartment.

Three, there had been three visits — the instruments and Michael’s delight in them and their shared laughter the only common language they needed. Then the week ended, and Michael returned to Bremen. He had been staying with his grandmother while his parents were on holiday in France. How did he communicate this to Abu Mustafa? But he had.

Michael said he had been living in Berlin the last two years, studying something called Arabic Studies at university. So many times he’d thought of visiting his old friend, but he worried Abu Mustafa wouldn’t remember him. After university he planned to join the Foreign Service — a good way to see new places and perhaps one day help shape Germany’s relationship with the Middle East. A man can speak your language and still speak to you from another universe: imagine seeing history as something you could influence, how must that feel? Michael continued to speak, seeming not to expect a response to anything he was saying. At the moment Germany had a very limited official presence in Syria but surely that would change in the course of his lifetime and he hoped one day to be in Damascus, which he referred to as ‘your Damascus’.

‘I am Syrian, yes, but before that I am Palestinian,’ Abu Mustafa said. ‘We were forced to leave in 1948, the Nakba.’ The look of discomfort on Michael’s face made him add, ‘Germany would accept me as a Syrian refugee but not as a Palestinian one.’

‘It’s complicated for Germany in ways outsiders can never understand,’ Michael said.

‘I think we understand.’

There was silence then, that German silence of double-glazed windows, people sealed up in their own lives. The phone had come off its charger. Abu Mustafa plugged it back in, re-started it, but the ancient device would take a long time to power on and until then there would only be this silence unless one of them found a way out of it.

‘Of course, I’m grateful to be here,’ he said.

‘Can I ask why you had to leave?’

‘There was a war.’

‘Yes. Of course.’ He glanced at the photographs on the dresser, the ones that Abu Mustafa had kept at the back of a drawer for so many months after his arrival. ‘I should have said, I’m sorry you had to leave your home. Twice.’

He wanted to embrace Michael then, but he would have to stand up to do that. ‘You were always a good boy.’

‘It must get so lonely.’

‘Allah is always with me.’

‘I’m glad you have Him.’ A gracious way to announce your own disbelief, though he was sorry to know that Michael didn’t have the only pillar of support that could never be taken from you no matter the cruelty of the world.

Michael stood and moved his chair so he was sitting side by side with Abu Mustafa. ‘I want you to see something.’

He had walked in with a leather bag slung over one shoulder which was now on the ground. He unbuckled its clasp and pulled out a tablet. There was a website, he said, which gathered sounds, recordings, from all over the world. Here, we can go to Damascus — tell me which neighbourhood you lived in there, we’ll find it. A few seconds later he said, ok, there’s nothing from there but there are thirty-one recordings from different parts of Damascus. Do you know Abu Antar’s cafe? No? But let’s listen.

He pressed something on the screen and the voices came out from the machine, words indistinct but the sound unmistakable of Arab men talking together, voices overlapping, a rising and rising tempo and then many voices joining together in laughter. The sounds stopped. Michael apologised. Perhaps he shouldn’t have played it. He didn’t mean to make Abu Mustafa miss Damascus.

‘No, I miss my friends at Shaam — the cafe in Sonnenallee.’

Michael touched his sleeve. ‘Yes, of course. Damascus is in Berlin also.’

What a strange thing to say. ‘My knees and this third floor apartment have made me enter a third exile.’

‘The Middle East in Berlin — that’s what I’m working on.’ Perhaps he hadn’t understood. He typed something new into the website and a map of Berlin appeared. ‘Thousands of sound recordings for this city, you see? But how many have people speaking Arabic? If you search for ‘Arabisch’ within Berlin look what you get.’

The website made no sense to Abu Mustafa but he nodded as if he understood.

‘So I thought, I want to go around the city and record all the sounds of Arabic and upload them here. I thought we could start here, with you and me, a Syrian refugee and a German man speaking together in Arabic. Is that ok? Can I record our conversation?’

Abu Mustafa sipped his tea. ‘This is for university? Or the foreign service?’

‘No, no, nothing like that. For me. For Berlin. It’s important. An acknowledgement of the different lives here. Imagine. . . imagine a new refugee from Syria comes here and can search for ‘Arabische’ or ‘Syrien’ on this website and find the sounds of home. And then they can know where to go to find those sounds. I mean to places like Shaam, which can be identified by name — I wouldn’t make your address public.’

After a long pause Abu Mustafa said, ‘We have other ways of finding each other when we arrive.’

‘Perhaps some of the younger ones. . .’

From the table beside him came the sound of the adhan, through the tinny speakers of the mosque shaped clock.

Both men looked at the clock — pink and gold, the brightest object in all of Berlin. Abu Mustafa reached out to switch it off. Again, that German silence. He rested his hands on both thighs, tilting his body forward as though preparing to stand.

‘Yes, of course, you have things to do. I’m sorry for taking up so much of your time.’ Michael got up, finally. ’But before I leave, just one thing. You really don’t have them anymore? Your instruments? They were like magic to me. That week at my grandmother’s, I was so bored, so lonely the whole time. Why had my parents left me? I felt abandoned. And then I walked in here and it was as if I was inside a Disney movie and everyday objects had come to life. And you were the magician who made it happen.’

Abu Mustafa walked into the kitchen with Michael following. He opened a cupboard and pointed to the top shelf. Michael stood on the kitchen chair and extracted both the instruments from behind an empty vase and the old transistor radio. He brought them down carefully, one by one, as if each instrument was a creature sleeping in his hands. There were spare batteries in the cutlery drawer. No plastic bag, but the bin liner would do.

‘Am I keeping you from your prayers?’

‘Allah is merciful and compassionate, and also patient.’

It took time and a trip by Michael to the hardware store, but eventually the instruments were restored: one was powered by an electric toothbrush, the other by a broken milk whisk. He switched on the whisk, stood back in surprise as the object he’d fashioned around it (kitchen-roll tube, cookie cutters, plastic bottle, teaspoon) moved in small steps across the floor to a jaunty beat — both the dancer and the music.

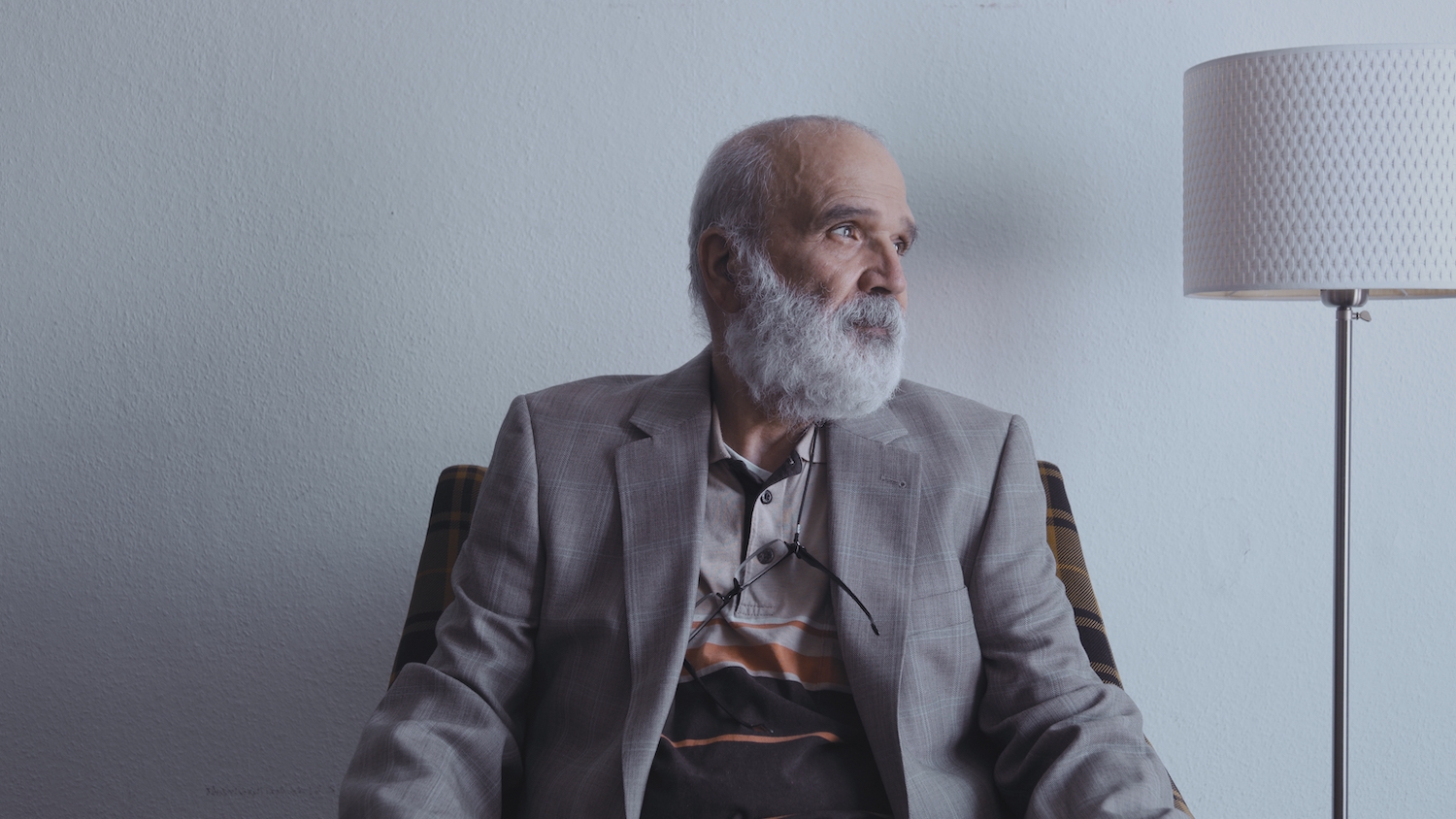

When pride returns after a long absence it shoots through the bloodstream. Abu Mustafa walked over to the clothes rack and took down the button-down shirt and his best jacket. Michael turned his back, but even so he went into the privacy of the bathroom.

While he changed he could hear Michael’s hand drumming on the base of a cooking pan. A poor sense of rhythm, but he could be taught. They could always be taught so long as they were willing to learn. He smoothed down his shirt in front of the bathroom mirror, practiced some words. When he returned to the living area he stepped into the space between the fan, the whisk, the toothbrush and cleared his throat. Michael held up his phone, his thumb hovering above the ‘record’ button.

Abu Mustafa nodded his head in readiness. The thumb touched the screen.

‘My name is Khaled Hamdan from Nablus and Damascus. This is my first composition in Berlin. The instruments are made from objects that were in my apartment when I first moved in. Thank you for listening.’

Then Michael spoke into the phone and translated his words into German, and English.

He switched on the fan, then the whisk, then the toothbrush. At first the sounds were separate, then they came together. A jingling, drumming, rustling and his humming voice threading through it. He gestured to Michael to hold his palm up and his own palm beat down on it. Skin against skin. The orchestra played his song.

—

Kamila Shamsie is an award-winning writer and novelist. Shamsie has published seven novels, including Best of Friends (2022) and Home Fire (2017).

Reprise by Kamila Shamsie was commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella to accompany the release of The Song (2022) by Bani Abidi.