So Far, and Yet So Near

Steven Bode

Graham Gussin's Remote Viewer was made twenty years ago this year. From a distance of two decades, Steven Bode reflects on how much it resonates with the present.

Projects

Watch Graham Gussin's Remote Viewer on FVU Watch.

Remote Viewer, Film and Video Umbrella’s turn-of-the-millennium commission by artist Graham Gussin, was filmed over a three-day period in the early autumn of 2001 – a landmark year that had already been advance-circled in the calendar by Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction opus, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Released in 1968, at the height of the NASA/Soviet space race, Kubrick’s film combines the white-hot cool of technocratic futurology with a subliminal shiver of Cold War paranoia, in the form of the threat posed to the crew of a spaceship by an all-seeing sentient computer that is able to second-guess humans’ thoughts and monitor their every move. A harbinger of contemporary anxiety about the coming ascendancy of artificial intelligence, this renegade ghost in the machine is also a pre-echo of a growing sense of unease with the ever-expanding virtual universe of digital telecommunications, whose infinite potential for frictionless, remote interaction is haunted by the spectre of equally unlimited, remote surveillance.

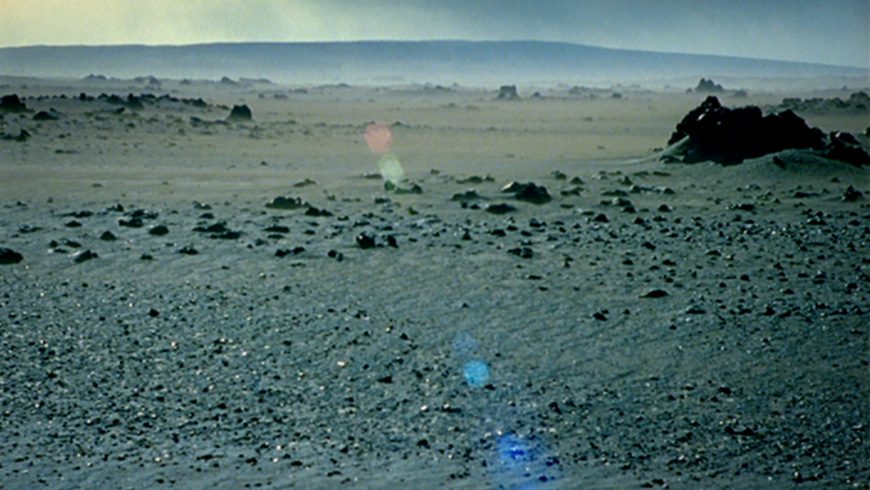

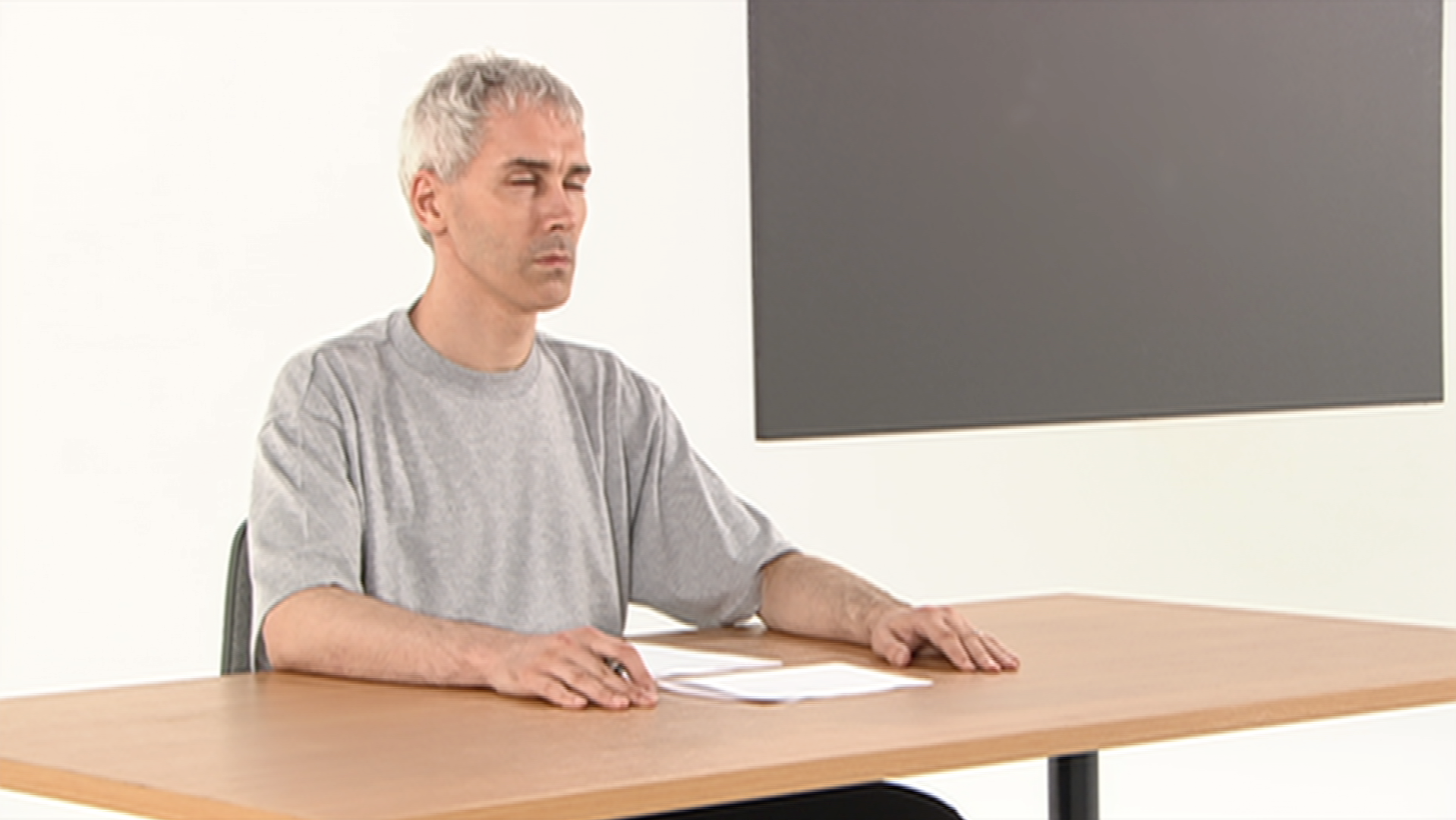

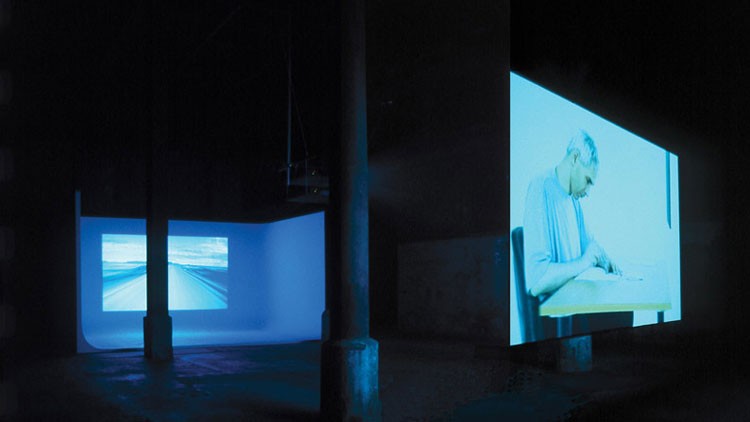

Remote Viewer is itself a space odyssey of sorts. On two large projection screens, facing each other inside the gallery, Gussin presents two companion sequences of video, each one shadowing and counterpointing the other. The first records the journey undertaken by Gussin, his camera operator (Bevis Bowden) and a local driver and guide to a place called Askja in the so-called ‘lunar desert’ of central Iceland. As that epithet implies, the landscape they pass through is unrelentingly barren and featureless – so inhospitable and off-the-beaten-track that it was used to prepare the Apollo astronauts for the eerie emptiness they would encounter in a moon landing. The second screen, by contrast, features footage of a man sitting at a desk in an equally deserted studio. Scribbling notes on blank sheets of paper, he uses his pen as much like a divining rod as a writing implement. His face is a model of furrowed concentration, and level with his sightline hangs a miniature blackboard on which he appears to be projecting his thoughts, and which floats free like an extension of his brain, or a prosthetic third eye.

The man, we learn, is a ‘remote viewer’: an individual trained to focus his mind on a location or a target over great distances. Over the course of the next thirty-five minutes, in a series of atmospheric, carefully composed scenes, deftly framed by cinematographer Martin Testar, we watch him going through the particular rituals and protocols that underpin this arcane activity; which, to an untrained eye, evokes both a process of iterative, cognitive code-breaking and something more akin to séance or numerology. The proximity of the two projection screens suggests a link between the different video sequences and the art of location finding being deployed, but there is no eureka moment, and a definitive connection is never established. Like the 360-degree panning shots that punctuate both sets of footage, the sequences oscillate around each other, the way a satellite orbits a planet, before returning to their start point and beginning another loop.

Parapsychology and space exploration are mirror images of each other in very many ways. The first manned forays into space that reached a crescendo in the 1960s were paralleled by a deepening interest in the paranormal, and a wider (counter-) cultural fascination with forms of extra-sensory perception, out-of-body experiences or other supernatural or unexplained phenomena. The emergent nuclear superpowers of the Soviet Union and the United States, facing off against each other through the long, tense years of the Cold War, ratcheted up their rivalry in the arms race and the space race by investing heavily in researching the potential of esoteric disciplines like mind control or telekinesis, with intelligence agencies on both sides of the Iron Curtain looking to add them to their arsenal of black ops. Remote viewers, too, were enlisted to ‘spy’ on hidden locations or uncover secret plans – the long-distance lens they were expected to supply taking its place among a panoply of listening posts and surveillance devices that proceeded to spring up over the surface of the planet, and whose ominous presence contributed to the mood of paranoia and conspiracy that characterised the time.

The coronavirus pandemic has made remote viewers of us all, to a certain extent. The safety net of the World Wide Web (itself the brainchild of Sixties military research), while still some way short of encompassing everyone, has enabled large numbers of people to work remotely, interact remotely, and experience places and situations vicariously. It has been a godsend at a time of crisis – a time of crisis, like the Cold War, that has unleashed its own mood of paranoia and conspiracy: about the virus and its causes, and some of the special powers to track and trace that have been invoked in its wake. Looking back at Remote Viewer from the distance of twenty years, it is extraordinary how resonant and prescient it seems. In an ideal world, it should be seen in a gallery – and I wish I could magic that to happen, now that galleries are once more opening their doors. But there is also a strange aptness to viewing it remotely – imagining yourself present in three dimensions as Gussin’s ethereal, otherworldly footage weaves its spell.

–––

Remote Viewer was commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Ikon Gallery. Supported by Arts Council England and the Henry Moore Foundation.

It was presented at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham and The Wapping Project, London in 2002.